The Trouble With Decolonial Thought

Aftereffects of colonialism are an unpleasant reality. But decolonial thought is not the solution to dealing with that reality.

Hello readers. Things have been hectic the past several weeks so I couldn’t post anything here, but below is a long read—an essay on decolonial thought. I wrote it out of unease with how the language of “decolonisation” has come to shape both academia and public discourse. It engages some complex ideas and touches on questions that may not interest non-specialist readers, though I hope I am wrong. To help you decide whether to read the piece or skip it, I’ve added a short preface.

Although most of the world’s nations are long decolonized, the aftereffects of colonialism persist, shaping how we think, imagine, and organise our institutions and laws. In recent years, a new set of ideas under the rubric of ‘decolonial thought’ has sought to confront these residues. Its aim is to ‘decolonise’ not only institutions and knowledge, but also imagination, culture, and even everyday politics.

That ambition gives decolonial thought its moral appeal, but also its tension.

Within universities, the movement calls for decolonising disciplines, syllabi, pedagogy, and institutions; beyond academia, it extends to culture, politics, and public space.

This essay suggests that, however well-intentioned, the academic drive for decolonisation may be weakening some of the very norms that keep scholarship strong, while its broader political version risks undoing many of modernity’s hard-won gains. It focuses in particular on decolonial thought’s attack on universalism, which is misread as a Eurocentric tool of domination.

Written for both scholars and general readers, the essay is primarily analytical, though occasionally polemical to press a point.

The full essay is published below.

The Trouble With Decolonial Thought

The term decolonization originally referred to the process through which colonized nations gained independence after the Second World War. But in recent years, decolonization has come to mean a project of scraping off the lingering aftereffects of European colonialism—from ideas, imagination, and inclination to speech, space, and solidarity. It has been developed under the rubric of decolonial thought within academia, and has found enthusiastic proponents in the wider world of public discourse and political activism.

This essay analyses decolonial thought within and beyond academia. Its purpose is to show decolonial thought’s narrow intellectual horizons and the problems associated with how it confronts the aftereffects of European colonialism.

The essay makes two arguments. Firstly, decolonial thought risks weakening the norms of rigour, responsibility, and openness that are necessary for sound academic scholarship. And secondly, it is legitimizing projects in the wider world that are undoing the hard-won emancipatory gains of modernity.

Objectives of decolonial thought

Decolonial thought has crystallised within the past decade; its leading text—On Decoloniality by Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh—was published in 2018. It has originated and developed within an elastic geometry that links a slice of Western academia with a distributed non-Western academia. Knowledge within this network is funded by Western academic capital and generated within the institutional apparatus comprising academic departments, publications, seminars, conferencing opportunities, and a conducive environment for dissent. Ideas produced within this network feature as much in academic publications as on social media, and from the latter they find circulation in wider public discourse.

Decolonial thought aims at an ambitious agenda of transformation in human affairs that it describes as decolonization. Its starting point is the claim that the West is essentially a colonial enterprise of unfreedom, and the latter’s dominant position in contemporary human affairs means that coloniality continues even as nations have become decolonized in the sense that they have become independent and have sovereignty over their affairs.

Furthermore, decolonial thought holds that over the past few centuries, ideas such as secularism, individualism, liberal democracy, and human rights have combined with the West’s economic and military power to subjugate the coloured humanity, suppressing the latter’s cultures, values, ideas, and identities. The suggestion is that although Western power has been steadily declining since the Second World War—a process that has accelerated in recent years—the global coloniality spawned by the West will end only when Western ideas are decisively abandoned.

Decolonial thinking attempts this by rejecting the claim that these ideas are universal in application, relevance or utility. It draws our attention to how Western practice has frequently been inconsistent with these ideas, abusing or falling short of them. This unsteady relationship gives us reason to believe that the claim that these ideas are universal is a ruse for Western domination, and whether the claim is made by the white man or his coloured comrades, the net result is that coloniality endures.

One task of decolonial thinking therefore is to show how these ideas have produced the Western practice of power. For instance, in decolonial discourse, liberalism and secularism have become synonyms of imperialism and discrimination; human rights the light that illuminates Western-practiced slavery; and liberal democracy the other side of a demolition machine, bombing Kosovo, invading Iraq, hanging Saddam Hussein and abandoning Afghanistan.

The decolonial method: guilty by association

The intellectual strategy that underwrites this critique reveals much about its limits.

The method of decolonial critique involves judging political ideas in terms of their association with practices and outcomes rather than by the internal logic of the ideas themselves. For instance, rather than showing how liberalism is inherently imperialistic, it takes the co-occurrence of imperialist behaviour and liberal principles within a Western state’s policy to argue, imply or treat as obvious the idea that imperialism is baked into liberalism. It does not encourage the possibility that the government of a liberal state may be using liberal principles to justify aggression on another nation. Although there are other methods, this associative logic is the staple of decolonial thought, becoming central to understanding both the appeal and the weakness of decolonial critique.

The decolonial rejection of the claim of Western universalism has two parts. As shown above, the first is that Western ideas are not universal. The second entails the argument that universalism itself is impossible or undesirable.

To suggest the former is to say that while humans belong to one species, there cannot be political ideas, values, and institutions that can potentially regulate the affairs of all of us. That while we are a single species, in the fashioning of our individuality and collective affairs we cannot transcend our location, culture, and identity. That the singularity of humanity cannot break the bounds of biology and enter the real world of social and political thought, if not organization.

The latter suggestion requires decolonial thinking to establish the desirability of non-universals rooted in particular locations, identities, and cultures over a universal. Decolonial thinking attempts to address this challenge by arguing that the particulars that have suffered and survived colonization and coloniality are superior, for instance, to the dominant universal of the West. Decolonial thinking develops this line of thought to provide the alternative to prevailing coloniality. The non-Western particulars share the commonality of suffering and survival; they bond through mutual sympathy and solidarity. As they work together to undo the coloniality, their worldviews interact—creating an ‘interverse’—and this ‘interversality’ produces a ‘pluriversal’, which is the alternative to universality.

These are innovative terms, but how do they stand up to scrutiny?

Let’s take ‘pluriversal’, the decolonial response to the modernist—and supposedly Western—universal. The decolonial ‘pluriversal’ retains coherence and therefore meaning only as long as it remains anti-Western. On its own, it succumbs to a centrifugalism generated by the logic of particularism: if each worldview rooted in a particular constellation of location, identity, and culture is as morally worthy as each of its peers, then, in the absence of a unifying animus, it must necessarily prioritize its own location, identity, and culture rather than coalition towards something greater—because nothing that can transcend identity, location or culture is either possible or desirable. Put differently, the pluriverse holds only as long as coloniality exists, and this raises the possibility that if coloniality did not exist, it would have to be invented.

Decolonial thinking finds ‘progressive’ to be a Western concept, reeking of universalism, so it positions itself as ‘emancipatory’. But its rejection of universality opens the pathway to parochialism. For instance, in India, the claim of universality as coloniality has legitimized the argument that Indo-Muslim rule was a form of coloniality executed by Islamic universality, a precursor to European colonization in the name of a universal vision.

The hard question that decolonial thought must confront is this: ‘Can a project that rejects universality avoid reproducing new forms of parochialism?’

Decolonialism in academia: the case of IR

The guilt by association method becomes particularly consequential when applied to academic disciplines. Within academia, the goal of this thought is the decolonization of knowledge. Unfortunately, this very broad agenda could be weakening disciplines.

To be sure, Western universities that developed on the degrading practices of colonization—slavery, displacement, dispossession, and genocide—are being rightly asked to confront their pasts and make amends. There are calls for returning artefacts in Western museums collected through loot and vandalism in the former colonies. These efforts are also seeing success. For what it’s worth, this writer has called for the archives pertaining to India lying in the UK libraries, archives, and private collections to be made digitally available to Indian researchers.

Pressuring Western institutions of knowledge to examine and acknowledge their colonial past would have formed a welcome limit to the decolonization agenda. But that agenda has overextended, moving from the machinery of knowledge creation to knowledge itself. And it is here that the decolonial project becomes problematic. This can be illustrated through the example of International Relations (IR), which is also the object of decolonial activism.

All academic disciplines have an ontological basis, that is, an object of enquiry that cannot be reduced to any other object without causing the discipline to lose the reason for its existence. The ontological basis for IR can be expressed negatively and positively.

Negatively, it refers to the absence of a sovereign authority above the level of sovereign states, also known as international anarchy, which produces patterns of conflict and cooperation in relations amongst territorially organized political societies, with wider consequences for human affairs.

Positively, it refers to the presence of geopolitical multiplicity, that is, the endless interactions of territorially organized political societies and the consequences of those interactions.

Human affairs across space and time have been regulated by international anarchy/geopolitical multiplicity, and this fact gives to IR a robust basis, akin to physics, biology, chemistry and economics. International anarchy and geopolitical multiplicity are to IR what matter is to physics, life to biology, reaction to chemistry, and wealth to economics. [More on IR’s ontologies can be found here and here.]

The ontological basis of IR can be found in the classical and contemporary political thought of practically any nation, region or civilizational area. For instance, ‘the law of fish’ (matsya nyaya) is another way of describing international anarchy while the mandala models of Asian political thinking express geopolitical multiplicity. IR’s ontological basis is therefore not only conceptually solid but it also has a material (geopolitical) foundation and is borne out by historical evidence.

However, it is only in the past century that this basis has found theoretical articulation and purposive development in university academic departments. This, in turn, has led to theories, pedagogy, methods of investigation, and protocols of judging the validity of knowledge, all in the service of programmes that award degrees in the discipline.

Recent research has corrected a previous notion that IR is a Western discipline in the sense that it originated and developed within Western academia. It has shown how IR has emerged through a truly global process of knowledge-creation. The contrast this historical picture presents with the disproportionate influence and visibility of IR scholarship that developed in the West shows the desirable direction critical scholarship can move in. At the same time, disciplinary histories written in recent years have revealed how IR’s knowledge infrastructure—academic departments, scholars, and journals—was concerned, not exclusively but prominently, with the management of colonial problems, which included delaying self-determination and defending racial segregation.

IR is not alone amongst the social sciences in being implicated in the colonial practice of power in this fashion, but there is a distinct way in which IR is amenable to the guilt by association method of decolonial thought. There is an obvious relationship between Western dominance of the modern world affairs and the disproportionate influence in IR academia of the variant of the discipline that has developed in the West. But it does not follow from this that IR as a whole is a handmaiden of coloniality. And yet, this is precisely what decolonial thinking in IR has been arguing: IR is Eurocentric, Western and a fundamentally colonial-imperial discipline.

Consider a sampling of illustrations that are deployed to support this argument:

Henry Kissinger was one of the American decision makers involved in committing war crimes in Vietnam as elsewhere. He also identified himself as a realist. So, the realist theory of international relations is an instrument of coloniality. Marxism is an instrument of coloniality because Marx welcomed colonialism (the tactical reasoning behind his position notwithstanding). Kant held racist notions, so his thesis on “Perpetual Peace” is not worth studying, and the liberalism that spawned from it is unsurprisingly imperialist. An important body of theoretical work in IR in the US and the UK developed under the patronage of the Rockefeller Foundation, so IR theory’s moral integrity is suspect. Most of the canonical IR theorists have been white and men. Most are also dead. Their writings represent the phenomenon of ‘dead white men’; they are dated, racist, and patriarchal—better left ignored. Political theorists such as John Locke and international law pioneers such as Hugo Grotius had professional, material, and ideological stakes in European colonial enterprises. And so political theory and international law are artefacts of coloniality.

The fact that many thinkers, theorists, and writers were entangled in colonial projects, and that IR’s institutionalisation has entailed benefitting from imperialism, are undeniable. But summary labelling, dismissal and stigmatizing have consequences.

Firstly, they could put the field on a slippery slope, leading to yet more absurd assertions. Here are a couple of hypothetical claims that flag the danger of what may come: ‘Jeremy Bentham coined the term ‘international’. His ideas went into the shaping of colonial rule on the Indian subcontinent. So, the basic concept of IR is tainted. David Hume was an early theorist of the balance of power. The concept of the balance of power became the basis of the concert system of Europe in the 19th century. Strategic stability in Europe made colonisation of the rest of the world less costly, so the balance of power is a relic of coloniality, and perhaps Hume is not worth studying.’

Secondly, they weaken the legitimacy of the notion, central to the study of ideas, that the ideas of thinkers one disagrees with, or indeed is positively uncomfortable with, have to be studied as things in themselves. That a cold analysis, not marked by affect, was necessary to give an idea its due. The associative logic stigmatizes this approach, dissuades scholars from unhesitatingly engaging with figures considered problematic, and robs the study of ideas of the thrill of an unexpected encounter and the joy of an unexpected discovery in the structure of a controversial figure’s thought.

But most damagingly, the guilt by association method risks turning critique of parts into an indictment of the whole. Imagine a curious outsider, a new student or a scholar from another discipline. For them, this method turns IR into a global political problem whereas the primary function of the discipline is to help us analyse the real-world problems of international affairs. The charge of coloniality makes IR appear like an unwanted discipline, either in need of wholesale reimagination or complete rejection.

The decolonial attack on IR—summary rejection, labelling and stigmatising of all that has been linked to colonialism: thinkers, theories, concepts, methods—has taken a toll on the field. It has tended to obscure the discipline’s foundations. There is a palpable unease with acknowledging that IR has a solid—and universal—object of enquiry, that is, international anarchy/geopolitical multiplicity. This is because decolonial thought claims that universality is a tool of western colonialism and coloniality.

Once IR’s two ontological forms are made suspect, the concerns arising from them tend to be viewed with suspicion as well. Thus themes like great power politics, alliances and coalitions, and security competition—the stuff of geopolitics—are becoming marginal. Instead, culture, identity, and location have become prominent issues. The classical caution against studying culture, ideas, identity and values abstracted from material structures of power within which they operate is no longer readily available. Decolonial analysis often sounds like accusation. And decolonial research validates more than it discovers. Decolonial thought makes IR turn on itself.

A result of this is that decolonial ‘IR’ scholarship focuses more and more on concerns that are, strictly speaking, either peripheral or external to what its object of enquiry permits. The arguments that decolonial thinking tends to make with regard to IR can be rendered analogically in this fashion: The guitar is made from matter. The guitar produces patterns of sound. So, physics should study music. Wealth can be accumulated. Over accumulation of wealth is greed. So, economics should be concerned with showing why greed is immoral. These two instances do not seem particularly outlandish. But consider where this line of thinking could go: biology is concerned with life. Life can be tragic. So, biology must study tragedy.

The distortions this method produces within academia have their analogues in public discourse, where historical figures get recast to fit contemporary ideological frames.

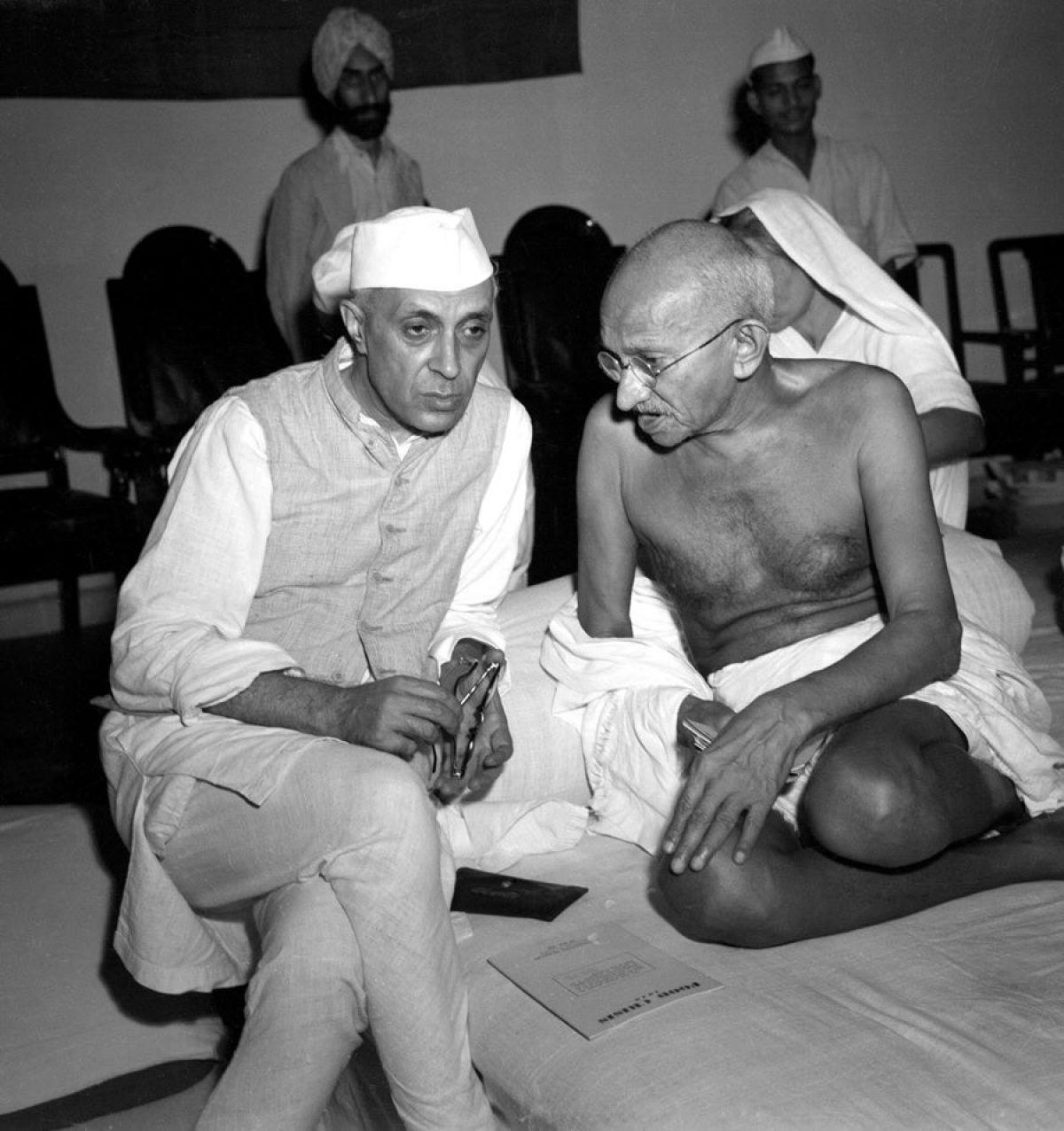

The decolonial assessment of Gandhi and Nehru

Take the example of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru: decolonial assessment of these anticolonial giants has entailed analytical shortcuts that reduce historical complexity to simplistic associations between figures, positions, and conviction.

Decolonial thinking entails an equation of caste and race. This move serves to scale anti-caste and anti-race justice movements up to the global level against the historical record of both forms having acquired a renewed lethality during European colonialism. Decolonial thought holds that the Savarna Man and the White Man colluded to produce a global regime of unfreedom, which was principally enacted within the vast expanses of the colony, and this provides a basis for a global justice activism that turns on the caste-race hyphenation.

Decolonial thought is post-structural in the sense that it assumes that structures are oppressive and need to be taken down. This starting position in analysis means that it does not differentiate between the complex historical trajectories and internal make-up of individual oppressive structures that give to each of them their distinctive features.

Caste and race are deeply different in how they code and reproduce unfreedom and degradation, and a serious engagement with their histories and internal makeup would show that while their equation can produce an emotional charge, allowing a trade of activism energy across the network of decolonial academia, its analytical tenability on account of their substantive differences is an open question—and a question that needs to be debated rather than assumed.

One of the moves on which the race-caste hyphenation rests is through critiques of Nehruvian secularism and Gandhi’s position on caste and views on the black people. An argument that has become increasingly common is that Indian secularism as fashioned by Nehru served to invisibilise caste in international affairs. This secularism projected a progressive image of India abroad, turning caste as a domestic problem. The official Indian resistance to ‘internationalization’ of caste at the Durban conference of 2001 was seen as an illustration of this position.

The question of the relationship between caste and international affairs throws a moral and analytical challenge to thought, policy, and activism. Historical research is showing an entanglement of caste and Indian foreign policy, and it is indeed the case that early writings on international theory from India approached caste as only an empirical phenomenon and not also a moral concern. But does the agenda of making caste visible in the conversation on India’s diplomacy and foreign policy require an attack on secularism? It does not, unless the argument, in another illustration of the guilt by association method, by implication is that Indian secularists have been ‘savarna’ men whose secularism is merely a cloak for the deployment of their privilege and influence to prevent caste from becoming accessible for critique and solidarity to the outside world.

The consequence of this style of reasoning is that the decolonial intellectual-activist appropriates the authority of judging the ‘savarna’. Here is how it can be rendered in the decolonial voice: ‘Your progressive responsibility as a secularist, an inclusive nationalist and an internationalist is not enough; you must also commit your politics to fighting caste on terms that I set out. Your identity as apparent to me in your gender, class, and caste will be my basis for judging your politics and its consequences, and I will not factor in your intentionality in this judgement.’

And now to Gandhi.

During the early period of his activism, Gandhi’s views reflected the prevailing model of a racial hierarchy in which the ‘brown’ man was placed below the ‘white’ but above the ‘black’. And it took him years to adjust his thought to the radical extent necessary to challenge its inequities in a serious fashion. His anti-caste activism did not match Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s. These limitations appear particularly stark in our times when the success of Gandhi’s anti-colonial liberation struggle has ceased to be an issue that needs analysis and judgement, affording an opportunity to examine his ideas on other concerns, which were not secondary in their moral worth but which had to yield to the struggle for decolonization in terms of policy priority.

Gandhian thinking was yoked to tactics and strategy in producing outcomes in the battles he made his own. Decolonial thinking abstracts Gandhi’s views on caste and race from this purposive element, reduces them to a version that makes them offensive to our times, and argues that they reinforce each other to be complicit in perpetuating the caste-race structural violence on the global scale. On this reading, Gandhi’s non-violence appears a false universal. The man is reduced to his ideas. He is placed in a kind of antagonism to Ambedkar that resembles, but is inconsistent with, historical reality, and it elevates, in decolonialism’s tribute to zero-sum rationality, Ambedkar’s stature by belittling Gandhi’s.

The problem with this reading is that to be attractive to those who are inclined towards decolonial thought, it must explain why two of the most successful figures in anti-racism struggle in modern times, whose leadership destroyed apartheid in South Africa and segregation in the United States (in other words, decolonized a large part of humanity), found Gandhi useful. The decolonial response has been to characterise Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr as ‘mainstream’, and elevate radical figures—such as Malcolm X—to link them with Ambedkar. A move such as this sharpens decolonial radicalism, but does it win external allies? Likely not, and this reveals something about how much thought decolonial thinking gives to the consequences of its positions and arguments for the wider world.

Decolonial thought and the Right

This animus against the Gandhi-Nehru duo feeds into the anger within that strand of the political Right in India which blames the duo for doing the Indian nation and the Indian majority a disservice. Here is a statement of that charge: ‘Nehru was a pseudo secularist; his internationalism came at the cost of Indian national interest. Gandhi’s interpretation of Hinduism emaciated India’s social body. He conceded Pakistan, leading to India’s partition, and his support for Nehru’s leadership deprived the country of Subhash Bose’s and Sardar Patel’s services. Across territorial integrity, cultural imbalance, and foreign policy setbacks, Gandhi and Nehru are responsible.’

This convergence between decolonial thought and populist discourse on the Right reveals a structural irony: arguments forged to contest domination can, when detached from their analytical and historical moorings, furnish legitimacy to problematic revisionism.

The contribution of academic decolonial thought to the development of right-wing popular discourse goes deeper. It has provided legitimacy to a revisionism in which colonialism is not kept limited to European empires but extended in the Indian context to pre-modern invasions and the geopolitics of pre-modern Indo-Muslim powers. The arguments of academic decolonial thought, although intended to assault Eurocentrism, have a structure of articulation that right-wing revisionism in India has made its own. The ‘colonial matrix of power’ has been read into a millennium of Indian history, legitimizing the notion that contemporary India is emerging from 1200 years of servitude; that while India became independent in 1947, its decolonization has only just begun.

One of the forms of that decolonization takes is monumental. In the West, it has taken the form of removal/disfiguring of Cecil Rhodes’ statues as well as those of the American Confederates. Gandhi’s statue too was vandalised in Johannesburg in 2015. This was done to protest his ‘racist’ views. Monumental and iconoclastic decolonisation of this sort finds a parallel with attempts to reverse the character of Muslim religious places in India, all against the backdrop of the Babri Mosque demolition, which has now been securely read as an act of decolonisation rather than an erasure of history.

But it does not end here. If decolonisation involves ending coloniality, then in the realm of geopolitics, that coloniality lies in the post-war South Asian interstate order, comprising the sovereign states of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. If the decolonial logic is extended—and decolonial thinking places emphasis on logic rather than on concrete socio-historical circumstances that set one situation apart from another—then the idea of ‘Akhand Bharat’ is also a decolonisation project. This project has no takers within India’s foreign policy establishment, but it has acquired noticeable circulation within the second rung of India’s ruling discourse. The idea lacks specificity, but in all its form, it questions the legitimacy of Pakistan and Bangladesh as ideas, if not as states.

Is decolonial thought really emancipatory?

The intellectual and political consequences of the decolonial orientation become clearest when viewed in relation to its historical counterparts. The decolonial agenda in academia has emerged five decades since most of the world became free of European colonialism (although cases such as Palestine’s remind of the detestable ugliness of colonialism and the political work that needs to be done). Thus, this phenomenon is not so much a case of academia catching up with real-world change as of the decline of the West as a dominant idea and the defensive position in which Western academic institutions have found themselves in the past two decades. They have conceded space to dissenting voices, most of which has been occupied by decolonial thinking. It would have been more desirable if that space had been populated by a variety of emancipatory visions rooted in rigorous analysis of concrete socio-historical situations that debated and collaborated to build a better world. Instead, that space has come to be dominated by a thought that reads critique through the lens of identity rather than argument. Decolonialism thus narrows the emancipatory horizon it seeks to articulate and expand.

To conclude, academic decolonial thought appears to be in a truncated relationship with the deeper and extensive social realities of the actually existing postcolonial world. Anticolonial liberation struggles that led to international decolonization were based on decolonial visions of national politics and international relations. And those visions are being implemented, although unevenly and amid contention, such as in the attempts to build an alternative international order under the rubric of the ‘Global South’.

It is striking that the animus found in contemporary decolonial thought was missing in the tallest leaders of the real-world decolonization project. Gandhi and Nehru both wanted Indians to lose anger towards the British and focus on constructive nation building and international solidarity. Neither Mandela nor King encouraged anti-White sentiments as the basis for continuing the struggle for racial equality. There is a model here for how the reckoning with colonialism should continue: by building upon the temper of leaders such as Ambedkar, Gandhi, Nehru, Mandela, and King—who coupled critique with reconstruction, and indignation with generosity.

The task, then, is not to abandon universality but to rescue it from empire—to imagine it anew as a shared human project grounded in mutual accountability. Mutual accountability because the moral high ground does not obtain in an imperfect world.

I think you are conflating belief in an external reality in which there are immutable, universal truths with consensus reality in which we negotiate and agree truth. The former is imperialist, the latter is not. Subjectivity and relativism don’t necessarily lead to a total collapse of value, they just lead to a destabilisation of power, and new power relations can be established within the context of relativism through negotiation. In other words, there is a middle ground.

I think part of the problem lies in the fact that many have also made the mistake of conflating relativism with external reality, by which I mean to say, and I think you hint at it, that relativism has become its own universalising principle, which leads to a similar impasse.

I think people have a hard time finding the middle ground because we are used to the stability of universals and we don’t like the responsibility of choice. But choice grants us both equality and agency. It just means we’ve got to face the difficult challenge of actually working shit out together.

I also think you’re exaggerating a bit. I don’t know anyone in real life who thinks we should exclude any work that has been tainted by colonial thought. People are just asking that the colonisation bit not be strategically left out, as it historically has been, and that a very small group of thinkers who aren’t representative of the whole of humanity not be used as the benchmark for our standards.

I also disagree that decolonial thought ’does not differentiate between the complex historical trajectories and internal make-up of individual oppressive structures’. Most of the decolonial works I have read - and I’ve read a few - are VERY focused on context. In fact I would say it’s kind of a hallmark feature which has been a standard in the field since the postcolonial days of early Spivak. Can the Subaltern Speak addresses the exact issue of contextualising culture that you raise.

I’m not saying that I agree with all decolonial thought or that I haven’t come across some pretty insufferable instances of relativist defeatism or narcissistic identity politics, but this is a rather uncharitable and kind of innacurate take on a complex field.

I do however agree that theory needs to be grounded in real world politics, and decolonial thought has too often been little more than a thought exercise. Although, essays like ‘Decolonisation is Not a Metaphor’ address this.

I also like your idea of rescuing universalism from empire, but I don’t think we should make the same mistake of assuming the pre-existence of universal standards. As I said before, there always has to be a recognition that universals are achieved through choice, that we do live in a relativistic world and and no singular culture has the unique purview of right and wrong, but that we better establish some ballpark ideas if we’re going to get along.

P.S I also don’t think the demolition of statues had anything to do with a desire to erase history, it’s about putting history where it belongs - in records, and not in gaudy, celebratory monuments lining our streets

I think the piece is interesting, and certainly some decolonial thinkers employ the “guilt by association” reasoning you mention. However, I have personally found decolonial theory to be much broader, and much more permissive, than you paint it here.

As someone who studied IR, I encountered a lot of decolonial authors. They did not disavow the discipline as a whole, but rather added a new lense, which students can use alongside realisme, neoliberalism, constructivism, etc, to analyse and better understand the systems and interactions that shape world politics.

Moreover, a very important part of the decolonial thinking movement, which I missed in this article, is the assessment that colonialism is not quite over— whether you look at America’s coups in Latin America, European meddling in Iraq or Libya, or even French oil Companies taking over oil reserves in Mozambique — the effects of colonialism are still present. The “structures” of world affairs, despite the end of direct colonial rule, were built during that time, and support one of the key practices of colonialism: ensuring resources flow from “The global south/former colonies/underdeveloped countries” (whatever you want to call it) to The West or The Global North.

Lastly, I do understand your point in that certain academic values are worth protecting, and that the colonial thinkers might go a bit far in their critiques and in their mission to strip away that which is perceived as colonial. However, the tendency to go overboard in the other direction from the previous ideological/cultural consensus is not uncommon at all when talking about ideology shifts or paradigm shifts. Personally, I think a thorough investigation of our values, ways of thinking, and explaining the world is beneficial. We are, after all, talking about centuries of colonial practices that shaped the way we think about race, development, and power. It is impossible for all racist and colonial notions to have been eradicated in 50 years, and our ideas, even those only “associated” with colonialism practises, SHOULD be tested for contagion. (Because colonialism is not so far in the past. Suriname, for example, gained independence in 1975. I have friends older than that).

They should also, of course, be allowed to pass that test, or otherwise evolve into something more fitting.

In short, I disagree that the colonial movement is harming academic values. After all, cultural relativism has existed since the 70’s, and was the first to challenge universalism. Universalism has thus far survived. Moreover, I don’t see decolonial thinkers denounce something like Human Rights. They merely criticise the West’s selective application of it— and rightly so! Whether Gaza, Sudan, or elsewhere, in practice, we see some humans have seemingly more rights than others.

Regardless, I enjoyed the read!